Since 2019, the Jupiter 1000 demonstrator, supported by NaTran, has been exploring Power-to-Gas technology to convert electricity into hydrogen on an industrial scale. In an article published in Energies magazine, Florent Brissaud, senior research engineer at NaTran R&I, head of R&D management at Jupiter 1000 and an expert in asset management for the energy transition, shares the lessons learned from several years of operation. Here are the main points.

Commissioned at the end of 2019 in Fos-sur-Mer, Jupiter 1000 is France's first megawatt-scale Power-to-Gas demonstrator. Led by NaTran, this multi-partner project tested two electrolysis technologies (alkaline and proton exchange membrane) supplied by McPhy Energy, powered by renewable energy from a wind farm operated by CNR (Compagnie Nationale du Rhône).

The aim of the project is to demonstrate the technical feasibility of these processes and capitalize on the initial operational feedback to support the industrial development of the Power-to-Gas sector. Florent Brissaud has published a scientific article in the journal Energies, providing the international community with an in-depth analysis of the operational challenges. Let's take a closer look at the key points of this article.

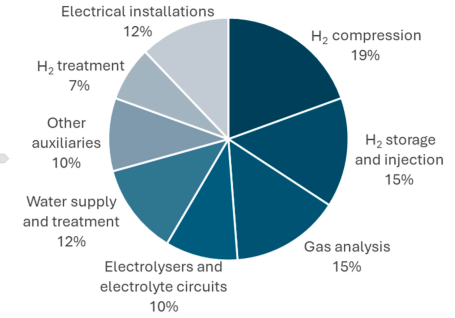

Over the operating period, Jupiter 1000's Power-to-Hydrogen installations suffered almost 50 failures. Contrary to popular belief, electrolysis-based hydrogen production systems are not the main source of downtime.

The data collected reveals that the majority of incidents involve technologically mature systems: compression (diaphragm compressor), storage and injection of hydrogen, particularly at the level of safety valves. Although this equipment is specifically designed for hydrogen, it is not always sufficiently tested for the particular properties of this gas.

"Electrolysers and associated circuits account for less than 30% of observed failures. This underlines the importance of reinforcing the reliability of the entire chain, and not just production technologies," adds Florent Brissaud.

An analysis of the causes reveals that almost half of all failures are of mechanical origin, often linked to the leak-prone properties of hydrogen. In addition, a quarter of the incidents originated in the design or installation of the systems, reflecting the still relative maturity of the sector at the time of commissioning of the Jupiter 1000 in 2019.

Source of failures observed on Jupiter 1000

The operation of Jupiter 1000 has also highlighted a number of maintenance challenges. The main obstacle identified was the limited availability of hydrogen equipment suppliers and service companies with the necessary skills.

The supply chain is still fragile: when a leak occurred in a water pipe feeding an electrolyzer, it took over 2 months to obtain a replacement part manufactured in Germany. Similarly, the replacement of a compressor diaphragm, although produced in France, took several months because of dependence on imported materials, notably from China.

The industry is also facing a shortage of qualified personnel (specialized technicians and engineers), resulting in high staff turnover and sometimes a loss of operational expertise. Over the 5 years of operation, NaTran R&I has had to call on former employees of subcontractors on several occasions to carry out certain tasks requiring in-depth knowledge of the installations.

Fortunately, NaTran, as a long-standing player in the gas sector, has been able to draw on the experience of its teams, accustomed to operating natural gas compressor stations, while developing specific hydrogen training programs.

Safety management on Jupiter 1000 required particular attention to the specific properties of hydrogen. This invisible, odorless gas has a wide flammability range (4 to 75% by volume in air) and requires 10 times less energy than natural gas to ignite. Its flame, almost invisible and emitting little radiant heat, makes fire detection particularly difficult without suitable equipment.

6 detector models, using different technologies, were tested on all installations operating with pure hydrogen. The results show that no single device is capable of detecting 100% of potential leaks. The recommendation resulting from these tests is to combine several detectors with complementary performances.

Furthermore, because of its small molecular size and low viscosity, hydrogen is particularly prone to leakage, including by permeation. Leak tests should therefore be carried out using helium or, failing that, hydrogenated nitrogen.

The risk of hydrogen embrittlement of metallic materials has also been the subject of dedicated tests on Jupiter 1000. Initial results indicate that the steels currently used to transport natural gas are mostly suitable for hydrogen transport under the operating conditions envisaged, although certain maintenance and monitoring programs will require adaptation.

As far as the electrolysers themselves are concerned, experience has shown that these rapidly evolving technologies require in-depth risk analysis right from the design phase. Indeed, both Jupiter 1000 electrolyzers had to be modified during the operational phase for safety reasons, underlining the need to develop specialized risk management expertise for these emerging technologies.

Based on this experience, Florent Brissaud identifies 5 challenges to support the industrial deployment of Power-to-Gas:

This feedback comes against a backdrop of accelerating development of the hydrogen industry in Europe. The European Hydrogen Backbone (EHB) initiative, supported by over 30 gas transmission operators including NaTran, aims to deploy a network of 53,000 km of hydrogen pipelines by 2040.

In France, the national strategy calls for the installation of 8 GW of electrolysis by 2035, with over 9 billion euros of public support. Against this backdrop, the lessons learned from pioneering demonstrators such as Jupiter 1000 are essential for securing and accelerating the transition to industrial scale.

As Florent points out, reliability and risk management are now critical factors, and some large-scale projects have already been scaled back because of these issues.

Our experience with the Jupiter 1000 project shows that, in addition to technological advances in electrolyzers, the entire industrial ecosystem needs to mature before Power-to-Gas solutions can be deployed on a large scale.

Scientific reference :

Brissaud, F. (2025). Reliability, Maintenance, and Safety of Power-to-Hydrogen: Lessons Learned from an Industrial Demonstrator. Energies, 18(23), 6184. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236184